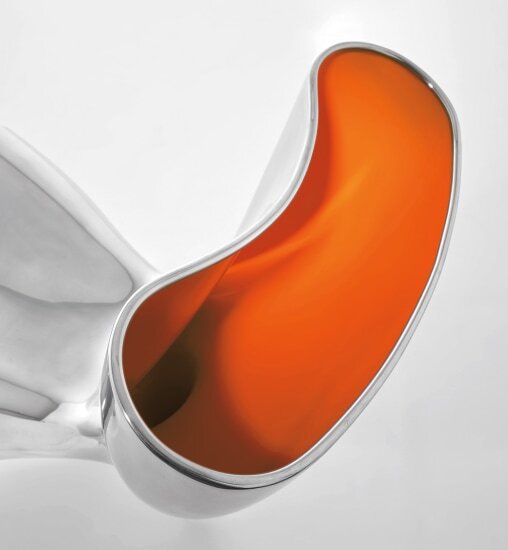

Marc Newson 'Orgone' Chair

photo: phillips

Marc Newson’s design education commenced long before he enrolled at the Sydney College of Art to study jewellery and silversmithing at age 19. Rather, he received his first lessons on form, materials, and process as a curious four‐year‐old kid, watching his uncle and friends take apart and rebuild one novel car after another in the garage attached to the Sydney home he shared with his mother and grandparents. By his teenage years, Newson was spending all his free time in the garage‐cum‐workshop, using his grandfather’s tools to construct soapbox racers of his own design. He cultivated a connoisseur’s expertise in classic Italian sports cars of the 1950s and 60s—the Ferraris, Bugattis and Alfa Romeos whose sleek lines conveyed not just speed, but also embodied the brio of postwar progress. This obsession only intensified as Newson entered adulthood, and he began amassing what has become a formidable collection of rare vintage racing cars. The shape, speed, and symbolism of the automobiles have had tremendous influence on Newson throughout his career as a designer of furniture, industrial objects, interiors, aircraft—even a vehicle of his own.

photo: phillips

More so than any of his other designs, the Orgone chair of 1993 channels Newson’s lifelong fascination with the streamlined ‘Continental look’ that characterises many cars designed during Italy’s postwar automotive renaissance. The chair’s compound curves create depressions on its seat and back that cradle the sitter’s body before swelling into fender‐like contours at either end of its wasp‐waisted form. With its sculptural shape and seamless aluminium surface, the Orgone chair recalls the aerodynamic forms made possible by Italian single‐shell coachbuilding techniques, first pioneered by the body stylist Pinin Farina in the 1940s. On the chair’s front, an open maw grins benignly to reveal a brightly coloured internal void, like the ovoid grilles found on many racing vehicles.

The Orgone chair (and its related Orgone stretch lounge) is also significant because it marked the culmination of years of experimentation with materials and techniques as Newson endeavored to produce a chair with the flowing metal surface and sensuous flanks of the vehicles he long admired. Despite his training as a silversmith, Newson found the project of an aluminium chair challenging, 'I had this vision of a liquious lump of metal, like a big blob of mercury. But I didn’t know how to do it. I didn’t have the expertise, the money, or the resources' (Alice Rawsthorn, ‘An Australian in Paris’, Blueprint, no. 104, February 1994, p. 31).

photo: phillips

Numerous earlier works show Newson attempting to develop what he was later able to achieve with the Orgone chair. One of his first major projects as a professional designer was the LC1 chair of 1986, a handmade, Neoclassical‐inspired chaise. To construct its metallic skin, Newson painstakingly cut, formed, and affixed hundreds of individual pieces of aluminium over its fiberglass body using rivets. While the resultant patchwork effect lacked the precision and smoothness Newson was seeking, he would revisit the technique the following year with his aluminium-clad Pod of Drawers, and further refine the process for his now-famous Lockheed Lounge chaise in 1988. With his Coil chair and Feltprototype chairs of 1989, Newson introduced the hourglass form later used by the Orgonechair, one wound from a continuous thread of aluminium wire and the other covered with a shell of thick felt. The Wicker chair and lounge followed in 1990 as Newson continued to explore the car‐like shape, now in rattan and with an open bottom. By this time, Newson was returning to the seamless metal furnishing designs that had vexed him before. Teaming up with skilled metalworkers in both Sydney and Paris, he was able to produce prototypes of the hollow Event Horizon table, whose polished aluminium surface and enameled inner void prefigure his Orgone series of seating.

photo: phillips

Fittingly, it was Newson’s passion for collecting vintage cars that would lead him to discover the means by which to make his vision for the Orgone chair a reality. In 1992, while hunting down a 1959 Aston Martin DB4 to add to his collection (a legendary British car wrapped in a sleek, Italian‐designed body), Newson visited Body Lines, an Aston Martin restoration shop outside of London. There, he encountered aluminium fabrication specialists trained in the advanced panel‐shaping techniques developed by famed Italian coachbuilding workshops (carrozzerie), and, suddenly, a light went off. 'I had always dreamed of taking a flat sheet of metal and bending it like a piece of Plasticine into a complex, three‐dimensional form', Newson recalled of his initial struggles with large‐scale metalworking. 'This specialised skill really only exists in two contexts, the production of aircraft in the traditional manner, and the production of car bodies in carrosseries' (Alison Castle, Marc Newson Works, London, 2012, p. 557).

Working with these master body shapers, Newson could beat and bend sheets of aluminium into the contiguous forms of the Orgone chair and stretch lounge; he even used them to fabricate a new edition of the aluminium Event Horizon table. By bringing his inspiration full circle back to the means of its production, Newson was finally able to create the chair he had dreamed of since his earliest days as a designer.